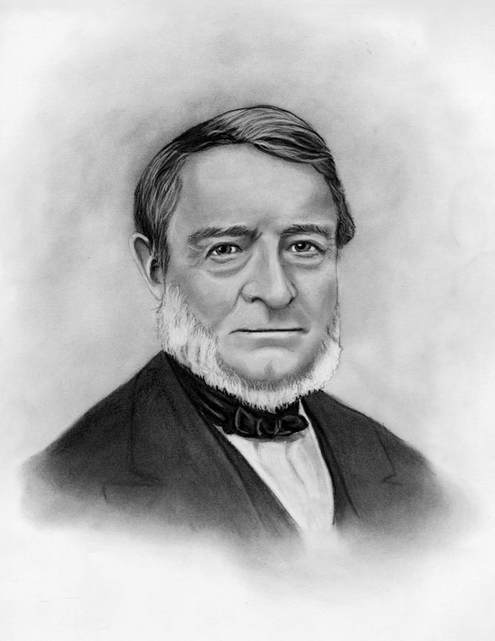

Samuel Joseph May

Samuel Joseph May was born into a well-connected Boston family, graduated from Harvard University (1817) and Harvard Divinity School (1820), and became the only Unitarian minister in Connecticut (1822). He married his lifelong partner, Lucretia Flagge Coffin, in 1825. William Lloyd Garrison abruptly converted him to immediate abolitionism in 1830; they became lifelong friends. Years later, Frederick Douglass commented they were “devotedly attached” to one another. Rev. May assisted Garrison in founding the New England Anti-Slavery Society (NEASS) and was a founding member the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS), where he served with Lewis Tappan and recorded his observations of Lucretia Mott.

He championed Prudence Crandall’s quest to educate Black schoolgirls (1832-3), published the abolitionist newspaper, The Unionist (1833), and helped with the organization of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (1834). Lydia Maria Child dedicated her signature book, Appeal in Favor of That Class of Americans Called Africans, to him.

In 1834, Rev. May converted his internationally recognized mentor, Dr. William E. Channing, to abolitionism; Channing’s resulting Slavery, though not radical enough for many, was nevertheless an important intellectual advance for abolitionism. Rev. May was hired as a General Agent and Corresponding Secretary for the NEASS (1835-6), hosted Sarah and Angelina E. Grimke when they spoke from his pulpit (1837), and praised the work of Abby Kelley Foster.

Tolerance and civility were characteristics of Rev. May; he tried, unsuccessfully, to avert the 1840 AASS breakup. Theodore Dwight Weld commented that Rev. May was the only abolitionist who “had not been poisoned by this fierce feud.”

In 1845, after serving parishes in Connecticut and Massachusetts, Rev. May accepted what was to become his final ministry, in Syracuse, NY. There he became acquainted with both Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman. His national prominence was acknowledged when the “Barn Burner Democratic/ Conscience Whigs” asked him for an opening prayer at their 1848 Buffalo convention, where he supported Gerrit Smith for president.

Rev. May, along with Gerrit Smith and Rev. Jermain Wesley Loguen, were instrumental in the 1851 rescue of the runaway slave William Jerry McHenry, arrested under the Fugitive Slave Act. Thereafter, he staged annual “Jerry Celebrations,’’ portraying this rescue as another “Boston Tea Party.” Rev. May is depicted on the “Jerry Rescue” monument in downtown Syracuse, NY.

By 1830, Rev. May had recognized that racial prejudice, not only financial self-interest, perpetuated slavery in the U.S., long after its prohibition elsewhere. He was dedicated to racial equality, not just abolition; he included African-Americans in his meetings (unlike many abolitionists), assisted hundreds of fugitive slaves in eastern Connecticut (1834) and Syracuse (from 1845), served as president of the Syracuse Fugitive Aid Society, toured settlements of former slaves in Canada for the AASS, founded one of the earliest Freedman’s Relief Associations (1862), and promoted Radical Reconstruction, especially suffrage, education and land distribution to former slaves.

He died in 1871, eulogized by Bishop Jermain Loguen, Gerrit Smith, and William Garrison who said “…without his encouraging words and zealous co-operation, I should have lost much of the inspiration….”

In addition to abolition, Reverend May championed women’s rights & suffrage, inter-racial and other educational reforms, pacifism, temperance, welfare of the under-privileged [proposed a graduated income tax, assisted the Onondaga Nation and several other disadvantaged], and liberal religion. He was a moral giant ahead of his time.

Don Milmore, M.D., M.A.

2017

He championed Prudence Crandall’s quest to educate Black schoolgirls (1832-3), published the abolitionist newspaper, The Unionist (1833), and helped with the organization of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (1834). Lydia Maria Child dedicated her signature book, Appeal in Favor of That Class of Americans Called Africans, to him.

In 1834, Rev. May converted his internationally recognized mentor, Dr. William E. Channing, to abolitionism; Channing’s resulting Slavery, though not radical enough for many, was nevertheless an important intellectual advance for abolitionism. Rev. May was hired as a General Agent and Corresponding Secretary for the NEASS (1835-6), hosted Sarah and Angelina E. Grimke when they spoke from his pulpit (1837), and praised the work of Abby Kelley Foster.

Tolerance and civility were characteristics of Rev. May; he tried, unsuccessfully, to avert the 1840 AASS breakup. Theodore Dwight Weld commented that Rev. May was the only abolitionist who “had not been poisoned by this fierce feud.”

In 1845, after serving parishes in Connecticut and Massachusetts, Rev. May accepted what was to become his final ministry, in Syracuse, NY. There he became acquainted with both Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman. His national prominence was acknowledged when the “Barn Burner Democratic/ Conscience Whigs” asked him for an opening prayer at their 1848 Buffalo convention, where he supported Gerrit Smith for president.

Rev. May, along with Gerrit Smith and Rev. Jermain Wesley Loguen, were instrumental in the 1851 rescue of the runaway slave William Jerry McHenry, arrested under the Fugitive Slave Act. Thereafter, he staged annual “Jerry Celebrations,’’ portraying this rescue as another “Boston Tea Party.” Rev. May is depicted on the “Jerry Rescue” monument in downtown Syracuse, NY.

By 1830, Rev. May had recognized that racial prejudice, not only financial self-interest, perpetuated slavery in the U.S., long after its prohibition elsewhere. He was dedicated to racial equality, not just abolition; he included African-Americans in his meetings (unlike many abolitionists), assisted hundreds of fugitive slaves in eastern Connecticut (1834) and Syracuse (from 1845), served as president of the Syracuse Fugitive Aid Society, toured settlements of former slaves in Canada for the AASS, founded one of the earliest Freedman’s Relief Associations (1862), and promoted Radical Reconstruction, especially suffrage, education and land distribution to former slaves.

He died in 1871, eulogized by Bishop Jermain Loguen, Gerrit Smith, and William Garrison who said “…without his encouraging words and zealous co-operation, I should have lost much of the inspiration….”

In addition to abolition, Reverend May championed women’s rights & suffrage, inter-racial and other educational reforms, pacifism, temperance, welfare of the under-privileged [proposed a graduated income tax, assisted the Onondaga Nation and several other disadvantaged], and liberal religion. He was a moral giant ahead of his time.

Don Milmore, M.D., M.A.

2017