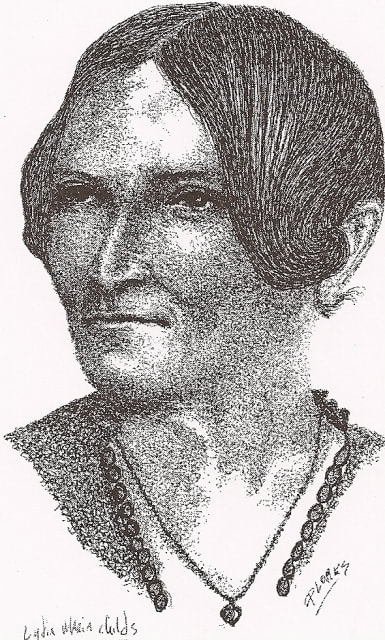

Lydia Maria Child

Lydia Maria (Francis) Child was born on February 11, 1802 in Medford, Massachusetts. Her literary career began at age twenty-two when her first novel, Hobomok: A Tale of Earlier Times, was published. Other works followed Hobomok, including a second novel, The Rebels, a children’s magazine, The Juvenile Miscellany, and domestic guides such as The American Frugal Housewife. In 1828, Lydia Maria married David Child, a lawyer and editor of The Massachusetts Journal.

Child’s work as an abolitionist began in the early 1830s after her introduction to William Lloyd Garrison, who was just beginning his own career in the fight against slavery. Unlike Garrison, Child was cautious in her embrace of the anti-slavery cause and spent three years researching the topic before finally committing herself completely to the movement.

In August 1833, at the height of her success in Boston literary circles, and after years studying the subject of slavery, Lydia Maria Child published An Appeal in Favor of that Class of Americans Called Africans. The first book-length anti-slavery work of its kind, An Appeal bravely challenged all of the assumptions and prejudices of its day regarding the question of slavery – including the economic, historical, social justifications for the institution. The work was painstakingly researched and its arguments thoughtfully organized and presented. Child was praised by her supporters for the comprehensiveness of the work and for her willingness to address issues many overlooked or avoided, such as racial prejudice in the North, the particularly difficult position of female slaves in relation to their white masters, and the questions of integration and inter-racial marriage. Child’s outspokenness came at a price. A once adoring public immediately cancelled subscriptions to her children’s magazine causing her to resign her position as editor, her domestic guide, The Mother’s Book, suddenly went out of print, and her place of honor in Boston’s literary world was revoked as former mentors and friends ostracized her.

Though Child depended on her writing to make a living for herself and to support her radical, though unreliable, husband, she never regretted her move into the world of abolition. She spent the rest of her long life and career writing and working to secure the rights of those pushed to the margins of American society. Her legacy includes works dedicated to the fight to end slavery, to secure the rights of free blacks after the Civil War, in protest against the mistreatment of Native Americans, and in support of the movement for equality for women.

Lydia Maria Child died in Wayland, Massachusetts on October 20, 1880.

Child’s work as an abolitionist began in the early 1830s after her introduction to William Lloyd Garrison, who was just beginning his own career in the fight against slavery. Unlike Garrison, Child was cautious in her embrace of the anti-slavery cause and spent three years researching the topic before finally committing herself completely to the movement.

In August 1833, at the height of her success in Boston literary circles, and after years studying the subject of slavery, Lydia Maria Child published An Appeal in Favor of that Class of Americans Called Africans. The first book-length anti-slavery work of its kind, An Appeal bravely challenged all of the assumptions and prejudices of its day regarding the question of slavery – including the economic, historical, social justifications for the institution. The work was painstakingly researched and its arguments thoughtfully organized and presented. Child was praised by her supporters for the comprehensiveness of the work and for her willingness to address issues many overlooked or avoided, such as racial prejudice in the North, the particularly difficult position of female slaves in relation to their white masters, and the questions of integration and inter-racial marriage. Child’s outspokenness came at a price. A once adoring public immediately cancelled subscriptions to her children’s magazine causing her to resign her position as editor, her domestic guide, The Mother’s Book, suddenly went out of print, and her place of honor in Boston’s literary world was revoked as former mentors and friends ostracized her.

Though Child depended on her writing to make a living for herself and to support her radical, though unreliable, husband, she never regretted her move into the world of abolition. She spent the rest of her long life and career writing and working to secure the rights of those pushed to the margins of American society. Her legacy includes works dedicated to the fight to end slavery, to secure the rights of free blacks after the Civil War, in protest against the mistreatment of Native Americans, and in support of the movement for equality for women.

Lydia Maria Child died in Wayland, Massachusetts on October 20, 1880.