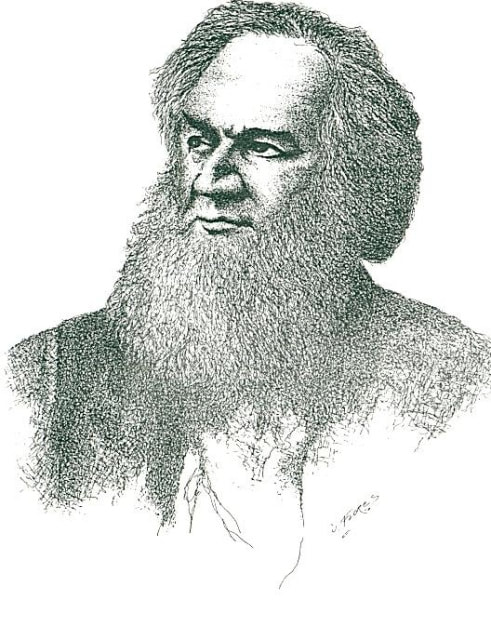

Gerrit Smith

Gerrit’s father, Peter Smith, had made his fortune as a partner with John Jacob Astor in the fur trading business in the late 1700s. The elder Smith used his wealth to purchase land tracts. Gerrit amassed land holdings in 54 counties in New York State as well as in several other states. He was the wealthiest landowner in New York State. Gerrit saw this wealth as a divine gift to be used for the benefit of others who were oppressed. As a steward of the family wealth he denied himself and his family in order to give to others who he saw as less fortunate.

Much of Smith’s philanthropy concentrated on liberating slaves. He complemented individuals’ efforts to buy freedom. He purchased individuals and families directly from slaveholders. He sent agents into the south to negotiate financial terms for freedom.

Smith was criticized by some of his colleagues for giving funds directly to individual persons as opposed to donating larger sums to organizations and societies with missions. Smith gave money to the abolitionists for traveling expenses and publications. By the mid 1840s, Smith had contributed over fifty thousand dollars (equivalent to five million dollars in 2002) to the antislavery movement. It has been estimated that in his lifetime Gerrit Smith gave away over eight million dollars. By today’s standard that would be equivalent to approximately one billion dollars!

Gerrit Smith believed that the Union should be preserved and that the Constitution prohibited slavery. He helped to organize, and participated in, anti-slavery conventions in many New York communities. His oratory and money were sought throughout the Northeast. He offered liberal funding to abolitionist newspapers over long periods of time, especially the efforts of his close friend Frederick Douglass with his North Star.

Smith opened his Peterboro home as a station on the Underground Railroad to fugitive slaves headed north. He aided hundreds of freedom seekers with his hospitality, his money, and his concern for human rights. Peterboro stood in the mid-nineteenth century as a model of interracial harmony, political concern for human rights, and human benevolence.

At first Smith believed that the abolition of slavery could come about through persuasion, but later advocated the use of political avenues to achieve abolition by supporting anti-slavery candidates. The current Republican Party had its origins in the abolitionist-oriented Liberty Party in the late 1830s. Gerrit Smith was a major influence in the party’s formation because he had broken away from the colonizationists who advocated exporting free blacks from the USA and the Garrisonians who avoided political activity. The Liberty Party eventually split into factions, one wing becoming the Radical Abolitionist party which advocated immediate abolition of all slavery in the US, and the Free Soil Party which advocated non-extension of slavery into new territories. By 1856, the Free Soil Party merged with anti-slavery men from the dying Whig Party to become the Republican Party which nominated Abraham Lincoln for President in 1860. Smith was nominated for President of the Unites States on abolition-based tickets four times, and worked hard at the local level for the election of Anti-slavery candidates.

As non-violent methods failed to turn the country away from slavery, Smith acknowledged that slavery might have to end by physical means – perhaps even through violence and bloodshed. Yet he continued to support peaceful means of resolution well into the 1850s.

In 1850 Smith and Frederick Douglass organized a convention in Cazenovia to protest passage of the pending Federal Fugitive Slave Bill. Smith wrote the resolution advocating that slaves use all means necessary to escape from slavery, including theft of materials for escape and force against owners.

Syracuse carpenter William (Mc)Henry, a fugitive slave known as Jerry, was arrested by authority of the Fugitive Slave Act. Gerrit Smith advocated a forcible rescue to demonstrate the violent opposition to the 1850 law. On October 1, 1851 Smith, Charles Merrick, Rev. Jermain W. Loguen, and Rev. Samuel J. May led abolitionists to free Jerry from jail and transport him to Canada.

In 1848 John Brown came to Peterboro to meet with Gerrit Smith and within the next decade he paid more visits. Five abolitionists from the Boston area plus Gerrit Smith, who would come to be known as the“Secret Six,” supported Brown’s anti-slavery activities.“I can see no other way,” said Smith.

Smith championed the need for the country’s healing once liberty was assured for slaves. He spoke out for benevolence to the southern states and to the slaveholders. Smith was one of three persons who paid the bail bond required to release Jefferson Davis, former President of the Confederate States of America, from jail.

In 1862 Smith won Lincoln’s original draft of the President’s hand-written First Emancipation Proclamation in a lottery to raise funds for the “Sanitary Commission for the Benefit of our Sick and Wounded Soldiers.” Smith donated the document to the State of New York.

Upon the occasion of Gerrit Smith’s death December 28, 1894, the New York Times wrote, “The history of the most important half century of our national life will be imperfectly written if it fails to place Gerrit Smith in the front rank of the men whose influence was most felt in the accomplishment of its results.” (NY Times, Volume XXIV, No. 7265, December 29, 1874)

Norman K. Dann, Ph.D.

Much of Smith’s philanthropy concentrated on liberating slaves. He complemented individuals’ efforts to buy freedom. He purchased individuals and families directly from slaveholders. He sent agents into the south to negotiate financial terms for freedom.

Smith was criticized by some of his colleagues for giving funds directly to individual persons as opposed to donating larger sums to organizations and societies with missions. Smith gave money to the abolitionists for traveling expenses and publications. By the mid 1840s, Smith had contributed over fifty thousand dollars (equivalent to five million dollars in 2002) to the antislavery movement. It has been estimated that in his lifetime Gerrit Smith gave away over eight million dollars. By today’s standard that would be equivalent to approximately one billion dollars!

Gerrit Smith believed that the Union should be preserved and that the Constitution prohibited slavery. He helped to organize, and participated in, anti-slavery conventions in many New York communities. His oratory and money were sought throughout the Northeast. He offered liberal funding to abolitionist newspapers over long periods of time, especially the efforts of his close friend Frederick Douglass with his North Star.

Smith opened his Peterboro home as a station on the Underground Railroad to fugitive slaves headed north. He aided hundreds of freedom seekers with his hospitality, his money, and his concern for human rights. Peterboro stood in the mid-nineteenth century as a model of interracial harmony, political concern for human rights, and human benevolence.

At first Smith believed that the abolition of slavery could come about through persuasion, but later advocated the use of political avenues to achieve abolition by supporting anti-slavery candidates. The current Republican Party had its origins in the abolitionist-oriented Liberty Party in the late 1830s. Gerrit Smith was a major influence in the party’s formation because he had broken away from the colonizationists who advocated exporting free blacks from the USA and the Garrisonians who avoided political activity. The Liberty Party eventually split into factions, one wing becoming the Radical Abolitionist party which advocated immediate abolition of all slavery in the US, and the Free Soil Party which advocated non-extension of slavery into new territories. By 1856, the Free Soil Party merged with anti-slavery men from the dying Whig Party to become the Republican Party which nominated Abraham Lincoln for President in 1860. Smith was nominated for President of the Unites States on abolition-based tickets four times, and worked hard at the local level for the election of Anti-slavery candidates.

As non-violent methods failed to turn the country away from slavery, Smith acknowledged that slavery might have to end by physical means – perhaps even through violence and bloodshed. Yet he continued to support peaceful means of resolution well into the 1850s.

In 1850 Smith and Frederick Douglass organized a convention in Cazenovia to protest passage of the pending Federal Fugitive Slave Bill. Smith wrote the resolution advocating that slaves use all means necessary to escape from slavery, including theft of materials for escape and force against owners.

Syracuse carpenter William (Mc)Henry, a fugitive slave known as Jerry, was arrested by authority of the Fugitive Slave Act. Gerrit Smith advocated a forcible rescue to demonstrate the violent opposition to the 1850 law. On October 1, 1851 Smith, Charles Merrick, Rev. Jermain W. Loguen, and Rev. Samuel J. May led abolitionists to free Jerry from jail and transport him to Canada.

In 1848 John Brown came to Peterboro to meet with Gerrit Smith and within the next decade he paid more visits. Five abolitionists from the Boston area plus Gerrit Smith, who would come to be known as the“Secret Six,” supported Brown’s anti-slavery activities.“I can see no other way,” said Smith.

Smith championed the need for the country’s healing once liberty was assured for slaves. He spoke out for benevolence to the southern states and to the slaveholders. Smith was one of three persons who paid the bail bond required to release Jefferson Davis, former President of the Confederate States of America, from jail.

In 1862 Smith won Lincoln’s original draft of the President’s hand-written First Emancipation Proclamation in a lottery to raise funds for the “Sanitary Commission for the Benefit of our Sick and Wounded Soldiers.” Smith donated the document to the State of New York.

Upon the occasion of Gerrit Smith’s death December 28, 1894, the New York Times wrote, “The history of the most important half century of our national life will be imperfectly written if it fails to place Gerrit Smith in the front rank of the men whose influence was most felt in the accomplishment of its results.” (NY Times, Volume XXIV, No. 7265, December 29, 1874)

Norman K. Dann, Ph.D.