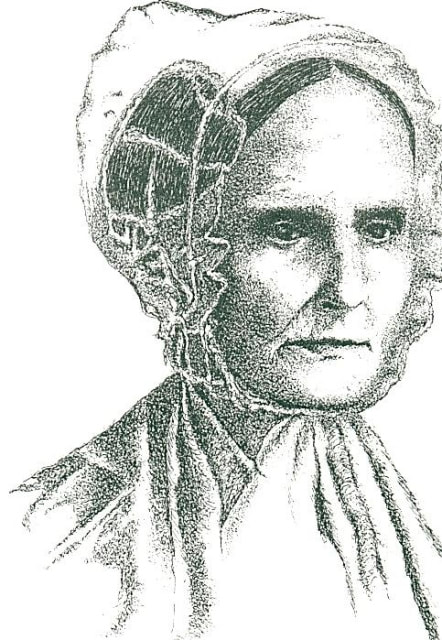

Lucretia Mott

Lucretia Mott was born Lucretia Coffin on January 3, 1793 to a prominent Nantucket Quaker family. Lucretia attended Nine Partners Boarding School, a Quaker institution in Dutchess County, NY, where she met her future husband James Mott. The couple married in Philadelphia in 1811. In 1821, in recognition of her powerful speaking abilities, Lucretia Mott became a Quaker minister. In 1827, the Motts and other Hicksite Quakers, followers of the minister Elias Hicks, split from their parent organization to take a stronger antislavery stand. From the beginning of her ministry, Mott blended the themes of abolition and women’s rights. She also advocated free produce, or the boycott of all products of slave labor (including sugar, cotton, etc.).

In December 1833, Lucretia Mott participated in the inaugural meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society, and she was the only woman to speak at the meeting. Afterward, she and a group of white and black women founded the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. From 1833 until it closed in 1870, PFASS was an interracial organization run by women. The support of Mott and PFASS was crucial for future female abolitionists, like Angelina and Sarah Grimké. Mott participated in all three National Anti-Slavery Conventions of American Women in 1838, 1838, and 1839. In 1838, Mott was present at the dedication of Pennsylvania Hall in Philadelphia, a new structure built for use by abolitionists. After the hall was torched by opponents during a meeting of the anti-slavery women, the mob targeted Mott’s home. Lucretia waited in her parlor for the mob to arrive, but an ally diverted the throng. In recognition of her leadership role among abolitionist women, the American Anti-Slavery Society and the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society appointed Mott as a delegate to the first World’s Anti-Slavery Convention held in London, England in 1840. In 1848, she attended the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, NY.

During her long anti-slavery career, Mott aided a number of fugitives, including Henry Box Brown and Jane Johnson, but she directed most of her energy toward ending the institution of slavery. She delivered anti-slavery lectures throughout the north, as well as in Washington, D.C., Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, and Virginia. In their annual fairs, she and other members of PFASS raised thousands of dollars to support abolitionist lecturers and publications. After the Civil War, Lucretia Mott continued her activism, advocating political and civil rights for African Americans until her death in 1880.

In December 1833, Lucretia Mott participated in the inaugural meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society, and she was the only woman to speak at the meeting. Afterward, she and a group of white and black women founded the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. From 1833 until it closed in 1870, PFASS was an interracial organization run by women. The support of Mott and PFASS was crucial for future female abolitionists, like Angelina and Sarah Grimké. Mott participated in all three National Anti-Slavery Conventions of American Women in 1838, 1838, and 1839. In 1838, Mott was present at the dedication of Pennsylvania Hall in Philadelphia, a new structure built for use by abolitionists. After the hall was torched by opponents during a meeting of the anti-slavery women, the mob targeted Mott’s home. Lucretia waited in her parlor for the mob to arrive, but an ally diverted the throng. In recognition of her leadership role among abolitionist women, the American Anti-Slavery Society and the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society appointed Mott as a delegate to the first World’s Anti-Slavery Convention held in London, England in 1840. In 1848, she attended the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, NY.

During her long anti-slavery career, Mott aided a number of fugitives, including Henry Box Brown and Jane Johnson, but she directed most of her energy toward ending the institution of slavery. She delivered anti-slavery lectures throughout the north, as well as in Washington, D.C., Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, and Virginia. In their annual fairs, she and other members of PFASS raised thousands of dollars to support abolitionist lecturers and publications. After the Civil War, Lucretia Mott continued her activism, advocating political and civil rights for African Americans until her death in 1880.

Additional resources

|

|

Talk: Lucretia Mott's HeresyIn celebration of Women's Equality Day, Carol Faulkner, Assistant Professor in the History Department at the Maxwell School of Citizenship, shared her research on Lucretia Coffin Mott. She covers Mott's life, activism and radical confrontation with American views of religion, race and women.

|