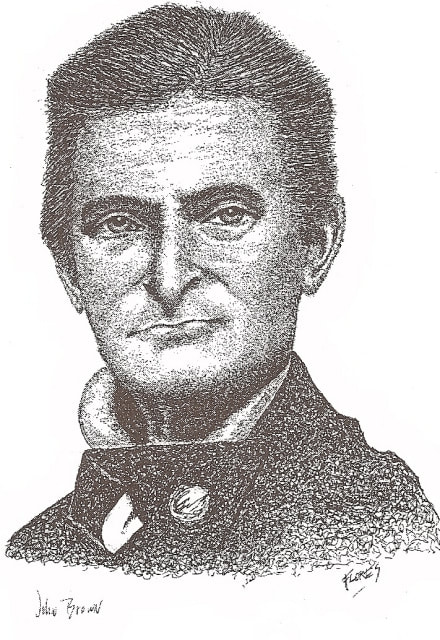

John Brown

Born in Connecticut on May 9, 1800, John Brown was raised in the Calvinist tradition by poor parents who taught him that divine predestination ruled lives. When the family moved to Hudson, Ohio, in 1805, John became friends with local black children and Native Americans. After witnessing the vicious beating of a young slave by his owner, he became a lifelong foe of slavery.

Following his aborted interest in being educated for the ministry, Brown married Dianthe Lusk in 1820 and became involved in several business ventures including surveying, tanning, and sheep farming. After moving to Randolph Township, Pennsylvania, in the mid 1820s, John was successful at opening a school for children, and a church, but his business ventures failed.

In the mid 1830s Brown moved back to the Hudson, Ohio, area with a new zeal for antislavery work which had been ignited by his subscription to and reading of William Lloyd Garrison’s newspaper The Liberator. Following the murder of abolitionist journalist Elijah Lovejoy by proslavery men in Illinois in 1837, Brown attended a religious service recognizing Lovejoy’s martyrdom at which Brown consecrated his life publicly to the destruction of slavery. Shortly, thereafter, he defied church segregation policy by inviting black people to join him in his pew. The racist reaction of local Ohio residents convinced him that only force could succeed in overcoming such intense prejudice.

John Brown grew to admire the nationally known abolitionist congressmen John Quincy Adams and Joshua Giddings, as well as the antislavery Liberty Party. As a nonconformist, Brown would not join an antislavery organization, but by 1848, he had met radical abolitionists Henry Highland Garnet, Jermain Loguen, Frederick Douglass, and Gerrit Smith, and was seriously considering the use of violence against the institution of slavery.

Brown’s attempts to help blacks included aiding them on the Underground Railroad, and his move to North Elba, New York, in 1849 to mentor black farmers participating in Gerrit Smith’s experiment in black enfranchisement. The passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law infuriated Brown, and he established the United States League of Gileadites to encourage slaves to resist their owners by force.

When the Kansas-Nebraska Bill was signed in 1854, Brown perceived a Slave Power plot to extend slavery into the new territory, and went there to fight for free soil. He fought against incursions into Kansans from slave states that bullied free soil settlers physically, socially, and politically. When Kansas was pacified by political means, Brown turned his focus toward Virginia as a fertile slave state in which he might instigate slave insurrection. The result was his attack on the United States arsenal at Harpers Ferry on October 16, 1859. That event sparked the Civil War and the eventual abolishment of slavery in the United States. Brown was subsequently tried for treason against the State of Virginia, and hanged for his effort to abolish slavery.

Following his aborted interest in being educated for the ministry, Brown married Dianthe Lusk in 1820 and became involved in several business ventures including surveying, tanning, and sheep farming. After moving to Randolph Township, Pennsylvania, in the mid 1820s, John was successful at opening a school for children, and a church, but his business ventures failed.

In the mid 1830s Brown moved back to the Hudson, Ohio, area with a new zeal for antislavery work which had been ignited by his subscription to and reading of William Lloyd Garrison’s newspaper The Liberator. Following the murder of abolitionist journalist Elijah Lovejoy by proslavery men in Illinois in 1837, Brown attended a religious service recognizing Lovejoy’s martyrdom at which Brown consecrated his life publicly to the destruction of slavery. Shortly, thereafter, he defied church segregation policy by inviting black people to join him in his pew. The racist reaction of local Ohio residents convinced him that only force could succeed in overcoming such intense prejudice.

John Brown grew to admire the nationally known abolitionist congressmen John Quincy Adams and Joshua Giddings, as well as the antislavery Liberty Party. As a nonconformist, Brown would not join an antislavery organization, but by 1848, he had met radical abolitionists Henry Highland Garnet, Jermain Loguen, Frederick Douglass, and Gerrit Smith, and was seriously considering the use of violence against the institution of slavery.

Brown’s attempts to help blacks included aiding them on the Underground Railroad, and his move to North Elba, New York, in 1849 to mentor black farmers participating in Gerrit Smith’s experiment in black enfranchisement. The passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law infuriated Brown, and he established the United States League of Gileadites to encourage slaves to resist their owners by force.

When the Kansas-Nebraska Bill was signed in 1854, Brown perceived a Slave Power plot to extend slavery into the new territory, and went there to fight for free soil. He fought against incursions into Kansans from slave states that bullied free soil settlers physically, socially, and politically. When Kansas was pacified by political means, Brown turned his focus toward Virginia as a fertile slave state in which he might instigate slave insurrection. The result was his attack on the United States arsenal at Harpers Ferry on October 16, 1859. That event sparked the Civil War and the eventual abolishment of slavery in the United States. Brown was subsequently tried for treason against the State of Virginia, and hanged for his effort to abolish slavery.