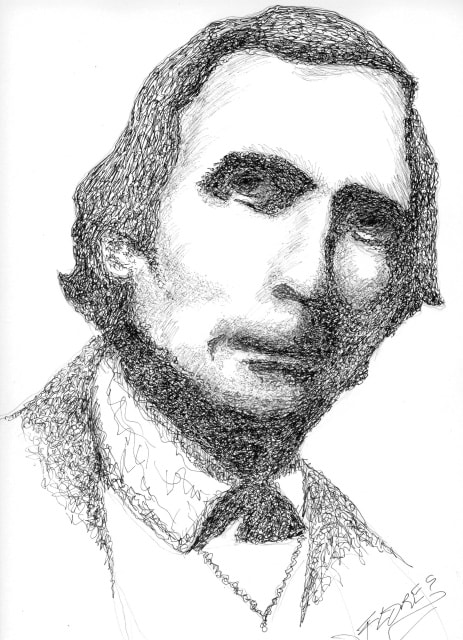

Jonathan Walker

Jonathan Walker (1799-1878), better known as the “Man with the Branded Hand,” was a Massachusetts-born antislavery author, lecturer, and agitator. A former merchant mariner known as “Captain,” Walker’s first major action against slavery came when colonization was considered a popular alternative to emancipation. In 1836, he went to Mexico with two young men, one his son, to meet Benjamin Lundy, a Philadelphia philanthropist who had purchased land near the Texas border as a potential colony for runaway slaves. While they waited for Lundy, pirates attacked Walker’s ship. Their young friend was killed, Walker was wounded, and their boat and a large sum of money were stolen. Ironically, Lundy never arrived.

The case that secured Walker’s antislavery reputation occurred in 1844. Walker and his family had moved to Pensacola, Florida, where Walker managed a railroad property and invited black workers to his home for meals. Already known for his anti-racist activities, bounty hunters captured Walker and seven fugitive slaves sailing for freedom in the Bahamas. In jail for one year, Walker was punished for “stealing slaves” by being branded with an “SS” by a United States marshal. This is the only known case of branding in American abolitionist history. Walker wrote about his experience in Trial and Imprisonment of Jonathan Walker at Pensacola, Florida, for Aiding Slaves to Escape From Bondage (1845). John Greenleaf Whittier’s poem about Walker, “The Branded Hand,” became nationally known.

Walker’s other contributions to abolition included hundreds of articles for William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator. Garrison’s respect for Walker is clear in an editorial he wrote and published in July 1845 upon Walker’s safe arrival in New York after his release from the Pensacola jail: “[Walker’s release] will create a thrilling sensation in the breasts of thousands who have deplored the imprisonment of the noble Walker as among the blackest atrocities of the age.”

For the next seven years, Walker lectured against slavery throughout the Northeast. One of his earliest antislavery speaking engagements was with Frederick Douglass in New Bedford. Walker’s speeches encouraged abolitionist activity; and he sold copies of abolitionist literature to raise funds for the movement. Accounts of his tours of New York and New England communities appeared in abolitionist newspapers.

In addition to his autobiographical account of his trial and imprisonment, Walker published A Brief View of American Chattelized Humanity And Its Supports (1846) and A Picture of Slavery for Youth (Undated). In 1852, Walker moved to the new state of Wisconsin. He wanted to establish a “commune” and a safe resting place on the Underground Railroad for fugitives from slavery going to freedom in Canada. In his final efforts to help African Americans, Walker left his new home, a Michigan orchard farm, in April 1864 and went to Virginia to help teach farm and trade skills to former slaves.

While Walker’s lasting fame came because of his suffering the rare punishment of branding, he devoted his life to ending slavery. His written record – his journal-like newspaper accounts and his three books – leave forever a history unlike any other abolitionist.

The case that secured Walker’s antislavery reputation occurred in 1844. Walker and his family had moved to Pensacola, Florida, where Walker managed a railroad property and invited black workers to his home for meals. Already known for his anti-racist activities, bounty hunters captured Walker and seven fugitive slaves sailing for freedom in the Bahamas. In jail for one year, Walker was punished for “stealing slaves” by being branded with an “SS” by a United States marshal. This is the only known case of branding in American abolitionist history. Walker wrote about his experience in Trial and Imprisonment of Jonathan Walker at Pensacola, Florida, for Aiding Slaves to Escape From Bondage (1845). John Greenleaf Whittier’s poem about Walker, “The Branded Hand,” became nationally known.

Walker’s other contributions to abolition included hundreds of articles for William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator. Garrison’s respect for Walker is clear in an editorial he wrote and published in July 1845 upon Walker’s safe arrival in New York after his release from the Pensacola jail: “[Walker’s release] will create a thrilling sensation in the breasts of thousands who have deplored the imprisonment of the noble Walker as among the blackest atrocities of the age.”

For the next seven years, Walker lectured against slavery throughout the Northeast. One of his earliest antislavery speaking engagements was with Frederick Douglass in New Bedford. Walker’s speeches encouraged abolitionist activity; and he sold copies of abolitionist literature to raise funds for the movement. Accounts of his tours of New York and New England communities appeared in abolitionist newspapers.

In addition to his autobiographical account of his trial and imprisonment, Walker published A Brief View of American Chattelized Humanity And Its Supports (1846) and A Picture of Slavery for Youth (Undated). In 1852, Walker moved to the new state of Wisconsin. He wanted to establish a “commune” and a safe resting place on the Underground Railroad for fugitives from slavery going to freedom in Canada. In his final efforts to help African Americans, Walker left his new home, a Michigan orchard farm, in April 1864 and went to Virginia to help teach farm and trade skills to former slaves.

While Walker’s lasting fame came because of his suffering the rare punishment of branding, he devoted his life to ending slavery. His written record – his journal-like newspaper accounts and his three books – leave forever a history unlike any other abolitionist.

Further information

|

Documents

|

Photos

|

Interested in more? Check out our mercantile!You can find video recordings of the ceremonies, as well as badges, books, buttons, magnets, mugs, and stationery at the Peterboro mercantile. Caps, tee shirts, journals, mugs, bags and more are available on NAHOF's cafepress shop.

|