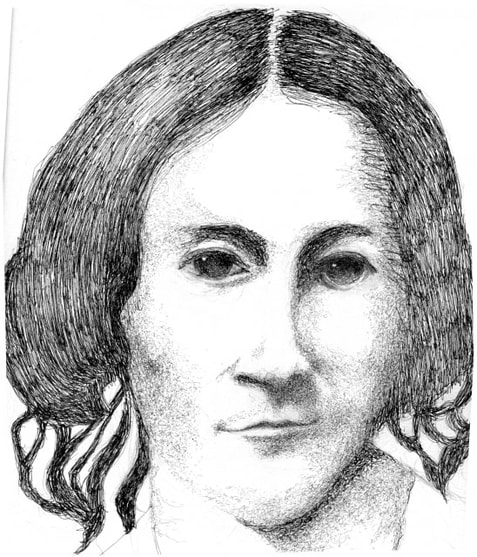

Myrtilla Miner

Myrtilla Miner was a leader in teacher training for free African American women, as she viewed knowledge and education as essential to ending slavery. Miner was born in Brookfield, New York, on March 4, 1815. She went to local schools before accepting a position as a teacher in Rochester, NY. In 1845, she moved to Providence, Rhode Island and spent the next two years teaching at the Richmond Street School. In 1847, she travelled to Mississippi and taught at the Newton Female Institute in Whitesville. While teaching there, Miner was appalled by the inhumanity of slavery and asked to teach young African American women, but was forbidden to do so. Because of her sympathy for the slaves, she was forced to leave Mississippi. In 1849, Miner returned to New York, where she taught in the town of Friendship, and developed a plan to train African American girls to become teachers for their people. She asked, “can slavery be removed when the free colored man remains degraded?” Frederick Douglass considered Miner’s proposal to be risky, stressing “the dangers she would encounter, the hardships she would have to endure and what seemed to me at the time certain failure of the enterprise after all she might do and suffer to make it successful.”

On December 3, 1851, Miss Miner began teaching six students in a small room, about 14 square feet square, in the frame house owned and occupied by an African American man in Washington, DC (present day corner of 11th and Washington Avenue). At the time, slavery was legal in the District of Columbia, but the Compromise of 1850 had banned the slave trade in the city. Due to intense racial prejudice, her greatest obstacle was finding a permanent location for the school. This local opposition necessitated three moves within two years. Finally, in 1853, Miner found a permanent venue for her school, known as the Normal School for Colored Girls. Prior to the Civil War, Miner’s school offered the only education beyond the elementary level available to African Americans in Washington, DC.

From the beginning of the school, Miner faced “rowdyism and incendiarism.” Much of this harassment targeted the teachers and students. Mobs attempted to burn down Miner’s school. The school met with formal opposition from the white community and city leaders such as former Mayor Walter Lenox. On May 6, 1857, Lenox bitterly denounced Ms. Miner and her school in the National Intelligencer. Despite a constant barrage of bigotry, harassment, and threats of violence, Miner remained defiant and determined to teach African American girls. In the end, she prevailed. One of her students remarked that she was “one of the bravest women I have ever known.”

Due to illness, Miner stepped down from teaching in 1857. By then, the Board of Trustees included Samuel Janney, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s husband Calvin Stowe, and her brother Henry Ward Beecher. In 1861, Miner moved to California in an attempt to improve her health while continuing to raise funds for the school. Unfortunately, a carriage accident in May 1864 resulted in critical injuries. She died in Washington, DC on December 17, 1864 and is buried in Oak Hill Cemetery in Washington, DC. Though her efforts to educate free African American girls were a moderate and indirect approach to ending slavery, the University of the District of Columbia traces the history of public higher education for African Americans in the city to Myrtilla Miner's School.

On December 3, 1851, Miss Miner began teaching six students in a small room, about 14 square feet square, in the frame house owned and occupied by an African American man in Washington, DC (present day corner of 11th and Washington Avenue). At the time, slavery was legal in the District of Columbia, but the Compromise of 1850 had banned the slave trade in the city. Due to intense racial prejudice, her greatest obstacle was finding a permanent location for the school. This local opposition necessitated three moves within two years. Finally, in 1853, Miner found a permanent venue for her school, known as the Normal School for Colored Girls. Prior to the Civil War, Miner’s school offered the only education beyond the elementary level available to African Americans in Washington, DC.

From the beginning of the school, Miner faced “rowdyism and incendiarism.” Much of this harassment targeted the teachers and students. Mobs attempted to burn down Miner’s school. The school met with formal opposition from the white community and city leaders such as former Mayor Walter Lenox. On May 6, 1857, Lenox bitterly denounced Ms. Miner and her school in the National Intelligencer. Despite a constant barrage of bigotry, harassment, and threats of violence, Miner remained defiant and determined to teach African American girls. In the end, she prevailed. One of her students remarked that she was “one of the bravest women I have ever known.”

Due to illness, Miner stepped down from teaching in 1857. By then, the Board of Trustees included Samuel Janney, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s husband Calvin Stowe, and her brother Henry Ward Beecher. In 1861, Miner moved to California in an attempt to improve her health while continuing to raise funds for the school. Unfortunately, a carriage accident in May 1864 resulted in critical injuries. She died in Washington, DC on December 17, 1864 and is buried in Oak Hill Cemetery in Washington, DC. Though her efforts to educate free African American girls were a moderate and indirect approach to ending slavery, the University of the District of Columbia traces the history of public higher education for African Americans in the city to Myrtilla Miner's School.