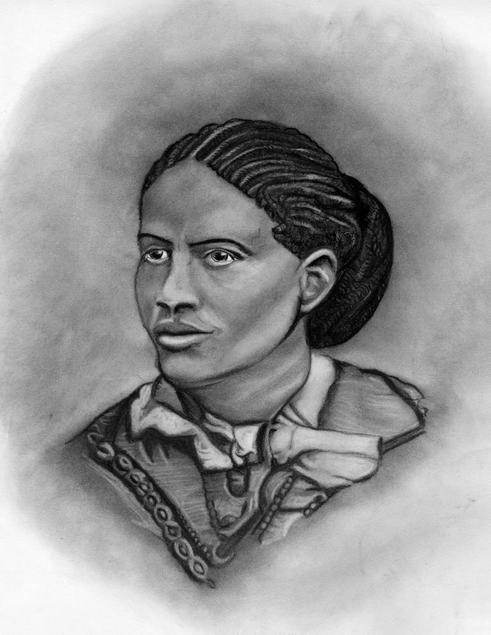

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

Frances E. W. Harper (1825-1911), nee Watkins, was the most prominent African-African female social reformer and writer in 19th-century America. Although she was born free in slaveholding Baltimore, she was orphaned as a toddler. As an orphan, she was subject to indenture and vulnerable to kidnapers, which meant she could easily have become a slave if her uncle, the Reverend William Watkins, Sr., had not taken her into his home and raised her as his daughter.

Watkins herself became an abolitionist orator after the passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law. In 1854, while teaching at a school in York, Pennsylvania, she was scandalized by the wrongful enslavement and death of a free black laborer named Edward Davis. By making her realize that she could have been him, Davis' case compelled her to identify even more closely with her enslaved people--an identification that resulted in her "pledging" herself "to the Anti-Slavery cause,” as she put it to close friend and colleague, William Still.

With the help of Still and others, Watkins entered the anti-slavery lecture circuit in Eastern Massachusetts and Rhode Island. While on that circuit, she published the first edition of her bestseller, Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects (1854). Shortly thereafter, she became a traveling lecturer for the Maine Daughters of Freedom, an organization of anti-slavery and temperance women. Watkins gained widespread acclaim as an abolitionist orator.

Watkins wove anti-slavery pieces such as "The Slave Mother," "Eliza Harris," "The Slave Auction," "A Mother's Heroism," and "The Fugitive's Wife" into a broader religious and moral framework. Watkins also published numerous abolitionist poems, speeches, essays and editorials- such as "Be Active" (1856), "Could We Trace the Record of Every Human Heart" (1857), "Miss Watkins and the Constitution" (1859), and "Our Greatest Want" (1859)-in anti-slavery and black newspapers and periodicals such as Frederick Douglass' Paper, the National Anti-Slavery Standard, and the Anglo-African Magazine.

In 1860, Watkins married Ohio farmer Fenton Harper, and took the name Frances Ellen Watkins Harper. Although her speaking engagements slowed, she retained her connection to the abolitionist world by remaining active in Ohio's anti-slavery and black convention movements--organizations to which she had initially been introduced in the late 1840s and early 1850s while teaching at Union Seminary, a precursor to Wilberforce University.

After Fenton's death in 1864, Watkins Harper returned to full-time abolitionism, and at the end of the war, translated her anti-slavery lecturing into helping the newly freed slaves. Known by this time as the "bronze muse," Watkins Harper published a number of works that focused on slavery and its aftermath in political, economic and religious terms. From the mid-1860s through the 1890s, Harper also concerned herself with the broad reconstruction of the nation. She championed the rights of blacks and women in her work with the women's rights movement. Harper died in 1911 and is buried in a historic African American cemetery outside of Philadelphia.

Marcia Robinson PhD

Milton C. Sernett PhD

Watkins herself became an abolitionist orator after the passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law. In 1854, while teaching at a school in York, Pennsylvania, she was scandalized by the wrongful enslavement and death of a free black laborer named Edward Davis. By making her realize that she could have been him, Davis' case compelled her to identify even more closely with her enslaved people--an identification that resulted in her "pledging" herself "to the Anti-Slavery cause,” as she put it to close friend and colleague, William Still.

With the help of Still and others, Watkins entered the anti-slavery lecture circuit in Eastern Massachusetts and Rhode Island. While on that circuit, she published the first edition of her bestseller, Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects (1854). Shortly thereafter, she became a traveling lecturer for the Maine Daughters of Freedom, an organization of anti-slavery and temperance women. Watkins gained widespread acclaim as an abolitionist orator.

Watkins wove anti-slavery pieces such as "The Slave Mother," "Eliza Harris," "The Slave Auction," "A Mother's Heroism," and "The Fugitive's Wife" into a broader religious and moral framework. Watkins also published numerous abolitionist poems, speeches, essays and editorials- such as "Be Active" (1856), "Could We Trace the Record of Every Human Heart" (1857), "Miss Watkins and the Constitution" (1859), and "Our Greatest Want" (1859)-in anti-slavery and black newspapers and periodicals such as Frederick Douglass' Paper, the National Anti-Slavery Standard, and the Anglo-African Magazine.

In 1860, Watkins married Ohio farmer Fenton Harper, and took the name Frances Ellen Watkins Harper. Although her speaking engagements slowed, she retained her connection to the abolitionist world by remaining active in Ohio's anti-slavery and black convention movements--organizations to which she had initially been introduced in the late 1840s and early 1850s while teaching at Union Seminary, a precursor to Wilberforce University.

After Fenton's death in 1864, Watkins Harper returned to full-time abolitionism, and at the end of the war, translated her anti-slavery lecturing into helping the newly freed slaves. Known by this time as the "bronze muse," Watkins Harper published a number of works that focused on slavery and its aftermath in political, economic and religious terms. From the mid-1860s through the 1890s, Harper also concerned herself with the broad reconstruction of the nation. She championed the rights of blacks and women in her work with the women's rights movement. Harper died in 1911 and is buried in a historic African American cemetery outside of Philadelphia.

Marcia Robinson PhD

Milton C. Sernett PhD